Monday Evening Six-Week Zoom Class with Dr. Susan Brown

February 19: 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. EST

February 26: 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. EST

March 11: 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. EST

March 18: 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. EST

March 25: 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. EST

April 1: 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. EST

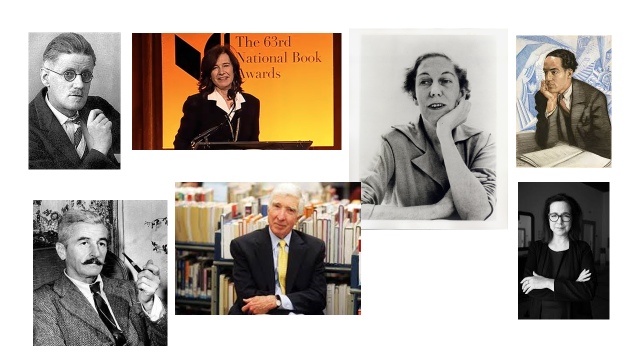

The great novelists also wrote short stories, often before they wrote their first novel. All the stories we’ll be reading are regularly anthologized in college literature texts, widely reviewed, and recognized as superb examples of the genre. Be inspired to take your writing project (memoir or fiction) to the next level by studying some of the most beautifully crafted and thought-provoking short stories in the Western canon. Sophisticated narrative devices are rarely detectable, but instead subtly and subliminally advance the themes of an accomplished writer.

A successful piece of literary fiction evokes two responses from a reader—emotional (the reader is moved in some way) and philosophical (the reader is provoked to reflect on themes pertaining to the human condition). Our goal in the workshop is to examine how a writer accomplishes both and then to think about how you might apply such devices and techniques in your own writing.

Questions for Discussion

1. What’s the Point of the Story? What Are Its Primary Themes?

In literary fiction, we are responding to two thematic levels—cultural and universal. The setting and events in the story offer a cultural–political, socio-economic, psychological, etc.—theme to consider. Also at play is one of the timeless universal questions. For example, “Is there a God?” “Is there a design in the universe?” “What is the self–essential or existential?” “What is beauty?” “What is love?” “What is the purpose of life?” “What is the nature of reality?” You get it. As you reflect on each story, consider both levels of theme.

2. Weekly Questions for Discussion: How did the Writer Accomplish the Emotional Impact and Impart a Thematic Message?

To prompt an examination of craft and narrative techniques in the stories, I’ll distribute questions about symbols, imagery, point of view, structure, plot, etc. for each story. Questions for each class will be emailed to you and posted in the class schedule below one week before each class.

The Schedule

As listed below, in the order we’ll be discussing them, are two stories I’m asking you to read for each class. For the first class there will be an additional short piece. I’ve grouped the stories loosely into six categories. In a separate email, I attached a copy of each story. And I’ll resend digital copies of the stories a week before each class with that week’s questions for discussion. Even if you read all these stories tonight, you’ll want to reread or review each story with my list of questions in mind before we discuss the stories in class.

Optional half-hour ad-on for the inspired!

As writers, I hope you’ll be inspired to experiment with some of the techniques you’ll be observing. Anyone inspired to experiment with a paragraph or two is invited to share with the group after the class, beginning class two. I’ll attach a suggested “assignment” to each week’s questions for discussion. I prefer brand new material inspired by the stories, or a revision of something you’re working on. P.S. this is not a feedback session. Just an opportunity to take a risk in a constructive and safe setting. And totally optional. Remember, no grades.

Class One: Rites de Passage, February 19, 2024 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. EST

The first thematic category we’ll investigate is the rites de passage genre. These are “coming of age” stories that depict the moment an event or experience triggers the shift from innocence to experience in the main character. In a rites of passage story, the reader is aware of two points of view—the adolescent character and the adult author. This creates dramatic irony, which is a narrative device typically at work in coming-of-age literature and satire. More on that later. The rites of passage story typically closes with an adolescent epiphany–which is different from and less sophisticated than the point the adult author wants to communicate. For this class, I’m asking you to read three pieces, two of which are very short. Sort of equals two regular length short stories.

1. “A & P,” by John Updike, first appeared in The New Yorker on July 22, 1961. The story was also published in Updike’s short story collection, Pigeon Feathers and Other Stories (1961).

2. “Salvation,” by Langston Hughes, is republished in countless anthologies as a stand-alone personal essay. It is an excerpt from Hughes’s memoir The Big Sea (1940).

3. “St. Marie,” by Louse Erdrich, is traditionally published as a stand-alone short story (first in Atlantic Monthly, 1984), but is also a chapter excerpt from Love Medicine (1984), which is a “novel” made up of separate stories about the intertwined fates of two families.

Questions for Discussion Class One: Rites de Passage, February 19, 2024

General Topics for Discussion

1. Thirty to forty percent of all anthologized short stories and memoir pieces have a protagonist aged 12 to 16 and were written by authors in their thirties and forties. Why?

2. Who is the audience for these three pieces? Twelve and thirteen-year-olds?

3. Think about the significance of names and titles in all three.

“Salvation”: Questions for Discussion

1. From whose point of view is the story told—a child or an adult?

2. Is this story about religion?

3. Why does the narrator cry at the end?

4. Why are there cliches in the work of this sophisticated writer?

“A & P”: Questions for Discussion

1. Why does Queenie buy only one item, and why is it a jar of fancy herring?

2. Why is the story set in an A & P rather than the equivalent of a store like Whole Foods?

“St. Marie”: Questions for Discussion

1. What is the role of fairy tales in this story?

2. Explain the relevance of the fishing imagery.

3. What are your thoughts about the “spoon” imagery at the end?

Due Next week (Feb. 26): Optional half-hour ad-on for the inspired!

Anyone inspired to experiment with the opening paragraph of a rites of passage story or memoir piece, is invited to share it with the group after the class during a half-hour continued session on zoom. Inspired by something in one of these stories (theme, structure, technique, etc.), please share either brand new material or a revision of revision of a work in progress. P.S. this is not a feedback session. It’s just an opportunity to take a risk in a constructive and safe setting. And totally optional. Remember, no grades. I will inspire you further with prompts and exercises at the end of class.

Class Two: The Heroic Quest, February 26, 2024 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. EST

The second thematic category we’ll investigate is heroic quest literature. The traditional examples from medieval romance depict a hero overcoming one insurmountable obstacle after another to obtain a treasure. In the most famous versions of the Arthurian story, the knights in Arthur’s court fight dragons and brave great trials to find the “Holy Grail.” What is most interesting about these legends, myths, and literary examples of heroic journeys in Western literature is the depiction of “the hero.” These two contemporary examples, “A Worn Path” and “Araby” explore the notion of what defines heroism in the Twentieth Century.

1. “A Worn Path,” by Eudora Welty, was published in Atlantic Monthly magazine in 1941 and received the second place O. Henry Award in that year. It’s one of Welty’s most famous short works.

2. “Araby,” by James Joyce, was written in 1905 and published as the third story in Dubliners (1914).

Class Two: Questions for Discussion, February 26, 2024 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. EST

General Questions for Discussion

1. List the traditional qualities of an archetypal hero in Western Culture. The anti-hero?

2. All cultures have heroic traditions and larger-than-life heroic figures. What do these stories say about heroism in the Twentieth Century?

“A Worn Path”: Questions for Discussion

1. Look at the progression of obstacles Phoenix must overcome to get the medicine for her grandson. What do you see?

2. Why does Phoenix Jackson choose a windmill as a gift for her grandson?

“Araby”: Questions for Discussion

1. What role does sexual awakening play in “Araby?” Many critics and teachers describe it as the primary theme.

2. What does the buckled harness in paragraph 3 symbolize. It was one of the last details Joyce added during several rounds of additions.

3. By the time Joyce wrote “Araby” in October,1905, he had permanently left Ireland, rejecting Irish Nationalism, the Catholic Church, and the straight-laced conventions of Irish society. He secretly regarded himself as a socialist and anarchist. Does he subtly reflect any of these ideas in this story?

4. Why doesn’t the boy buy a gift. He doesn’t have much money left, but presumably he has 8 pence, which is enough for something?

5. What is the significance of the conversation the boy hears at the close of the story?

6. What does Joyce mean by “vanity” in the final line, and who is actually making that analysis? The boy or the author?

Class Three Questions: Social Commentary, March 11, 2024 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. EST

Since the rise of the novel as a literary form (18th Century Britain), occurrences in the social order (politics, neighborhood feuds, domestic gossip) and an examination of social interactions has been a dominant theme in literature. While the British novel most famously addressed questions of class, marriage, and the domestic order (Dickens, Austen, Bronte, Thackery), American writers were quick to look at war, racism, crime and other disruptive elements in our history and culture.

1. “Good Country People,” by Flannery O’Connor was published in her short story collection A Good Man Is Hard to Find (1955).

2. “The Things They Carried,” by Tim O’Brien is the title story of The Things They Carried (1990), a collection of linked short stories about a platoon of American soldiers fighting on the ground in the Vietnam War.

Class Three Questions for Discussion: Social Commentary, March 11, 2024 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. EST

General Questions for Discussion

1. How is “tone” Central in these two stories? Tone in writing refers to the speaker’s attitude or “tone of voice.” Think of the different “tones of voice”: angry, blasé, whimsical, light-hearted, curious, sarcastic, deadpan, numb, curious, enthusiastic, etc. ad nauseum. How would you describe the narrator’s tone and in what way does the narrator’s tone contribute to the theme in each story?

2. What is accomplished by having multiple characters and/or multiple points of view?

“The Things They Carried”: Questions for Discussion

1. Why do Jimmy’s letters weigh eight ten ounces?

2. What are the possible meanings of “carry”?

3. Comment on naming.

“Good Country People”: Questions for Discussion

1. What is the symbolism of the salesman taking Joy’s leg? Think about how cliches work in the story.

2. How do the secondary characters function in this tale?

Class Four: Human Relationships March 18, 2024 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. EST

Much of literature from medieval oral poetry to contemporary drama and fiction explores human relationships—for example, the themes of romantic love, familial love, love of country, parental love, and friendship. “What is love?” “What is loyalty?” and “To whom does one owe the first responsibility—oneself, one’s family, one’s community, an institution, or a principle?” And what happens when these loyalties are in conflict?

1. “Welding with Children,” by Tim Gautreaux was published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1998 and the lead story in his short story collection, Welding with Children: Stories (1999).

2. “Friend of My Youth” by Alice Munro appeared in The New Yorker (1990) and as the lead story in her short story collection Friend of My Youth (1990).

Class Five: Autobiographical Fiction, March 25, 2024, 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. EST

Although writers typically take experiences and observations from their own lives as the starting point for a story or draw from an actual person as the model for a fictional character, some fiction is intended to be identified as autobiographical. In these novels and stories, all or most of the details and events have a real life corollary. In this sub-genre, the writer often overtly calls attention to autobiographical parallels and/or creates a confusion between reality and fiction.

1. “People like that Are the only People Here,” by Lorrie Moore was first published in The New Yorker and later published under the title “People like that Are the only People Here: Canonical Babbling in Peed Oink,” in her short story collection, Birds of America (1998). It is published as “fiction.”

2. “Glory Goes and Gets Some” by Emily Carter was first published in Open City magazine (1998) and later in a collection by the same title (2000).

Class Six: The Unreliable Narrator, April 1, 2024, 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. EST

The next stories we read explore the human experience through the point of view of an unreliable narrator. Famous examples of this device occur in “A Modest Proposal” by Jonathan Swift, Lolita by Vladmir Nabokov, Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, and The Great Gatsy by F. Scott Fitzgerald. In this literature, authors employ dramatic irony on steroids, and an unreliable narrator is typically a vehicle for satire. This genre requires extra critical attention from readers. Remember how many viewers failed to grasp the satiric intention of “All in the Family”?

1. “Rape Fantasies” by Margaret Atwood was originally published in The Fiddelhead in 1975, and subsequently republished in Atwood’s Dancing Girls & Other Stories (1977). The story gained greater attention and study when it was later anthologized in the 1985 edition of Norton Anthology of Literature by Women.

2. “A Rose for Emily” by William Faulkner was first published on April 30, 1930, in an issue of The Forum. The story takes place in Faulkner’s fictional Jefferson, Mississippi, in the equally fictional county of Yoknapatawpha.

A few suggestions about how to derive the most from this workshop:

First, I suggest you print each story to read it. Although we will look at passages on the shared zoom screen, if you have a hard copy, it will be easier to take notes as you read, follow the class discussion by page number, and locate your own markings, notes, and questions.

1. My main request is that you just read the assigned stories before the class. Even if you read a story decades ago in a high school or college, please enjoy it again with new eyes.

2. If you want to dive deeper, try to identify the themes and the point of each story. Why did these writers tell (invent) these particular stories? Literary fiction and memoir writers use the events and outcome of a narrative to illustrate their deepest insights into the human condition. A PhD in Literature is a Doctor of Philosophy.

3. To fully appreciate the craft in these stories, pay attention to narrative techniques–narrative voice, imagery, structure, plot, point of view, names, title, symbols, etc. Original literary fiction offers models which we can learn from.

4. The next level of close reading is more challenging: determine how the different narrative techniques advance a theme.

5. I will address all these points in the class discussion.

6. Except for reading the stories, everything else is optional, however. No required class participation. No tests. Just be inspired by good writing.

With any questions contact me at susansutliffbrown@gmail.com or call me at 941-855-0444